Table of Contents

- The Background

- The Stack

- The Process

- Results

- The Initial Database Design

- Useful Lesson:

- Next Steps

- Bibliography and Excellent Flask API Resources

The Background

During the time between university and my first job, I decided I wanted to undertake a project that would allow me to learn new and important web technologies. Building off of the very rough concept of the original [StepWise] ( /portfolio/steps/) I thought that learning how to develop a backend that could be used on cross-platform devices. The original vision was to try to create a community platform where people could place requests to the API to create new steps and challenges for other to try and undertake.

The Stack

- PostgreSQL

- Python / Flask

- SQLAlchemy / Alembic

- Heroku / AWS S3 Buckets

- OAuth 2 authentications with Auth0

The Process

Following the first two steps of this guide, I created a PostgreSQL database connected to Heroku. This guide taught some good production practices, and new technologies. This included database and virtual environment maintenance, as well as new concepts like ORM, database migration tools, and how to deploy databases to heroku. By using this reference in addition to a few others for reference, I was able to get a basic Flask API script working.

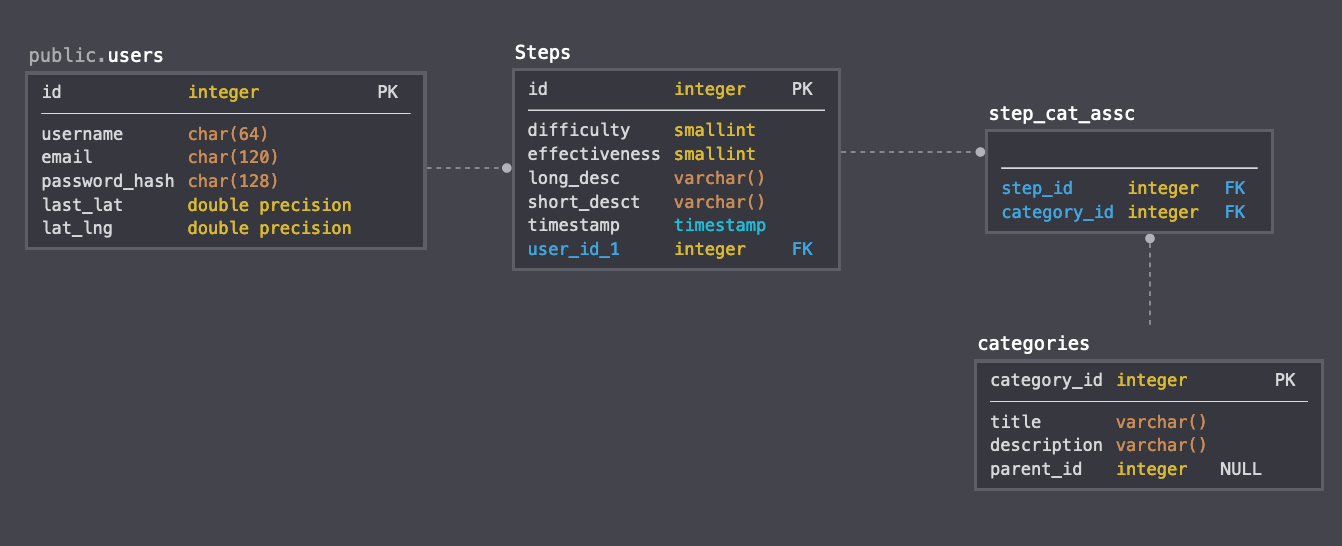

I then created table models in SQLAlchemy, for Users, Steps, Categories, and a Step_Cat association table for the many-to-many relationship. I used YAML to quickly fill these tables, and migrated the database to Heroku. The next step was to create simple RESTful Flask scripts to query the database, and return the information.

Overall the process took a few weeks partially because I was exploring lots of options both in stack and design, Additionally, it took a while because none of the guides I found online had a guide to make exactly what I wanted. Thus, I had to make sure to check other sources to ensure best practices, and to learn new elements that I would need to bring in to my project. This is one of the first projects I have made where I felt like I was brushing the dust off of certain websites to find the answers I needed.

In the end, I created an API that is fully hosted on heroku and connected to an optimized PostGres database.

Results

It works!

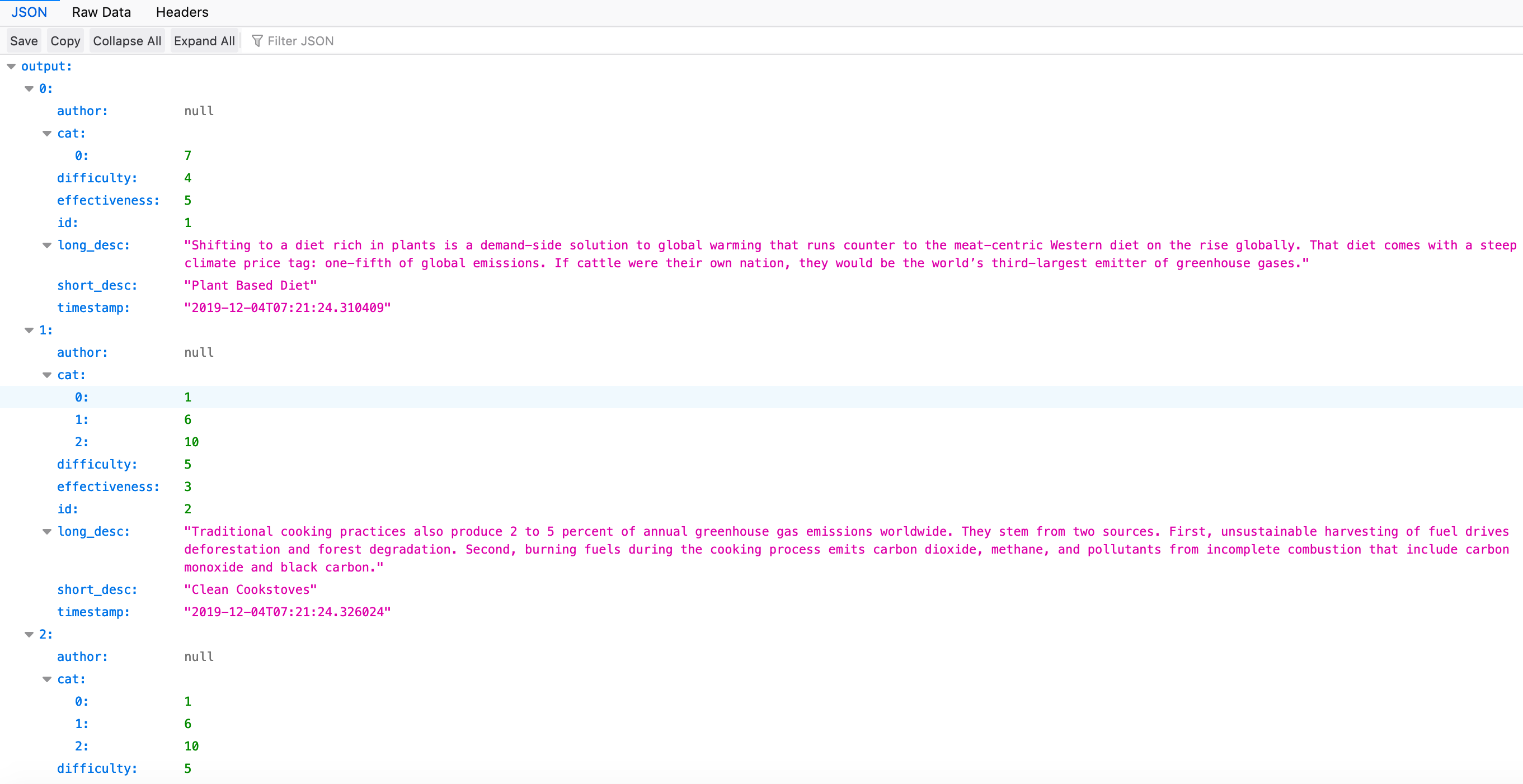

On calling ~.com/api/v1/resources/solutions/all. I get this result:

I additionally made paths to:

- Create a new user using a POST request. Or list all users using a GET request to the same place.

- Get specific solutions by adding a specific id as an argument.

- Render the home page HTML template, as a landing page

Furthermore, I added basic Auth0 authentication that limits access to user data unless the request contains a legitimate bearer token

The Initial Database Design

This was a very simple database design. To create the models looks something like what I’ve show below. A separate table (step-cat) was needed to be made to hold the many-to-many mapping between the “Steps” model, and the “Category” model, as steps could belong to multiple categories. The “Steps” table also has a user foreign key to map who created that step. A lot of time was spent trying to figure out how to best store hierarchial data, and ultimately, an “Ltree” data type was used - taking full advantage of Postgres, but is not reflected in this diagram.

Useful Lesson:

Setting up Models in SQLAlchemy

SqlAlchemy is an ORM (Object-relational mapping). It serves as an abstraction to SQL which allows for rich features, and writing code that can be easily migrated to different SQL types. By making a model, a PostgreSQL table is automatically generated, including references and dependencies.

User Table

class User(db.Model):

__tablename__ = 'users'

id = db.Column(db.Integer, primary_key=True)

username = db.Column(db.String(64), index=True, unique=True)

email = db.Column(db.String(120), index=True, unique=True)

password_hash = db.Column(db.String(128))

steps = db.relationship('Step', backref='author', lazy='dynamic', cascade="delete")

def __repr__(self):

return '<User {}>'.format(self.username)

def set_password(self, password):

self.password_hash = crypt.hash(password)

def check_password(self, password):

return crypt.verify(password, self.password_hash)

Note how the cascade is tied into the relationship, ensuring that deletions can occur without a foreign key violation. Furthermore, note that only the password hash is stored by using a simple hashing and hash checking algorithm.

Step Table

class Step(db.Model):

__tablename__ = 'steps'

id = db.Column(db.Integer, primary_key=True)

short_desc = db.Column(db.String(),nullable=False)

long_desc = db.Column(db.String())

difficulty = db.Column(db.SmallInteger) #1-7

effectiveness = db.Column(db.SmallInteger) #1-7

author_id = db.Column(db.Integer, db.ForeignKey('users.id'))

timestamp = db.Column(db.DateTime, index=True, default=datetime.utcnow)

cat = db.relationship("Category",

secondary=step_cat_assc, backref ="steps", lazy="dynamic")

Step / Category many-to-many table

step_cat_assc = Table('step_cat', db.Model.metadata,

db.Column('step_id', db.Integer, db.ForeignKey('steps.id')),

db.Column('category_id', db.Integer, db.ForeignKey('categories.id'))

)

This design was taken from best practices using SQLAlchemy here

Category Table

class Category(db.Model):

__tablename__ = 'categories'

id = db.Column(db.Integer, id_seq, primary_key=True)

title = db.Column(db.String(),nullable=False)

description = db.Column(db.String())

path = db.Column(LtreeType, nullable=False)

parent = db.relationship(

'Category',

primaryjoin=remote(path) == foreign(func.subpath(path, 0, -1)),

backref='children',

viewonly=True,

)

AS you can see, the “Ltree” was used to store paths to the parents. “LTreeType” uses a “Gist” or Generalized Search Tree in Postgres, which allow for incredibly fast access and manipulation of data in Postgres. I wanted to find a way to store hierarchial data, such that I could have categories and sub-categories and an efficient way to traverse between them. By using the LTree, I could query SQL for parents, grandparents or individual steps. I could additionally add branches, copy branches, replant a branch as a new tree, etc. A good resource explaining this data type can be found on this blog post.

Using YAML for batch PostgreSQL database additions

One problem that I found when working with postgres, was how to get a lot of data imported into the database at one time. I found an effective solution in using YAML text files, and a python YAML parsing library.

It’s really quite simple. Here are a few quick examples.

import_categories.yaml

title: "Zero Hunger"

description: "End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture."

---

title: "Good Health and Well-Being"

description: "Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages."

parent: 1

import_users.yaml:

username: "user1"

email: "test@test.com"

password: "password"

---

import_steps.yaml

short_desc: "Clean Cookstoves"

long_desc: "Traditional cooking practices also produce 2 to 5 percent of annual greenhouse gas emissions worldwide..."

difficulty: 5

effectiveness: 3

author_id: 2

cat:

- 10

- 1

- 6

By using data created in these YAML files, I can use the models I created earlier, parse them, and add them to the database like so:

from models import Category

for data in yaml.load_all(open('import_categories.yaml'),Loader = yaml.SafeLoader):

if 'parent' in data:

step = Category(title = data['title'],description = data['description'],parent=Ltree(str(data['parent'])))

else:

step = Category(title = data['title'],description = data['description'])

db.session.add(step)

db.session.commit()

With importing the categories, there was a necessity to check if a parent was specified, say for a subcategory. I have an ‘if’ statement which loops over each element in the yaml file, checks if there is an element named ‘parent’ and if there is, add it as an Ltree path.

Similarly, for users, the password hash is added as the user object is created. Obviously, this would only be used for testing purposes, as having passwords stored in plain text would be a very bad idea.

from models import User

for data in yaml.load_all(open('import_users.yaml'),Loader = yaml.SafeLoader):

print(data)

usr = User(username = data['username'],email = data['email'])

usr.set_password(data['password'])

print(str(db.session.add(usr)))

db.session.commit()

Finally, when adding the steps, there was an added complexity of adding multiple categories. This was accomplished by looping though each element in the ‘cat’ section of the yaml document, and adding them a category object by querying the category table for that id. After getting an list of category objects, I create the Step object and pass the list as an argument.

from models import Steps

for data in yaml.load_all(open('import_steps.yaml'),Loader = yaml.SafeLoader):

s = data

print(s)

cts = []

for i in s['cat']:

cts.append(Category.query.get(i))

step = Step(...args..., categories = cat)

db.session.add(step)

db.session.commit()

SQLAlchemy and Alembic

Another new tech concept I learned about was how to maintain database migrations using Alembic. Alembic is a database migration tool that automatically checks for changes in the database, and ensures that those changes are tracked and able to be followed. Futhermore, it’s directly ties in to SQLAlchemy, so it can tell when I alter my model. By ensuring that a clear upgrade/downgrade path exists, I can make sure that I can alter my table to previous revisions without breaking anything.

There are two most commonly used commands when using Alembic: migrate, and upgrade/downgrade. My understanding is that migrate tracks the changes and makes a script, and upgrade actually shifts the database to be the newer one. The problem is if you migrate and realize that your changes aren’t what you want. I found that running a ‘stamp-heads’ command is problematic because it created a duplicate migration script. If you choose to ‘stamp-heads’ to avoid upgrading, make sure you go into your scripts, and change both the “upgrade” and “downgrade” functions of the duplicate migration script to “pass”. I believe it may be possible to just delete the duplicate migration file, as long as you change the path of the newer file to have the downgrade id point to a lower revision that hadn’t been deleted, but I was not going to risk trying it.

It’s interesting how the internet hold few answers for hypothetical coding questions, and holds many more for real problems and errors that need solving.

Miscellaneous

- The OOP term ‘mixin’ describes a class that contained methods, for use by other classes without having to be the parent class. Basically a special type of multiple inheritance that gives classes a lot of extra functions or gives many classes one added function, but cannot exist on their own.

- What a REST API is:

- A REST API is comprised of Collections and Instances

- A RESTful server holds no information about context, that is, all the information needed to access the data is contained in the request itself.

- A lot of services call themselves RESTful but fail to do. There is disagreement about what a proper Restful endpoint looks like, but I made efforts to ensure that my links were all nouns and not verbs, furthermore, best practices were kept by sending appropriate HTML status codes.

- Becoming proficient with python decorators, which allow functions to be passed as arguments, and expands their functionality without modifying them. A very useful tool

Next Steps

This process of making a basic, hosted and running API was certainly interesting and a fun challenge. I found it rewarding to create and develop a backend of my own design, feed it resources, and have it return those resources on any device. I even built a functioning react-native app which called the API, and returned the results in a simple list.

Now I want to take this Go-Cart apart, and use its bones to make a Ferrari.

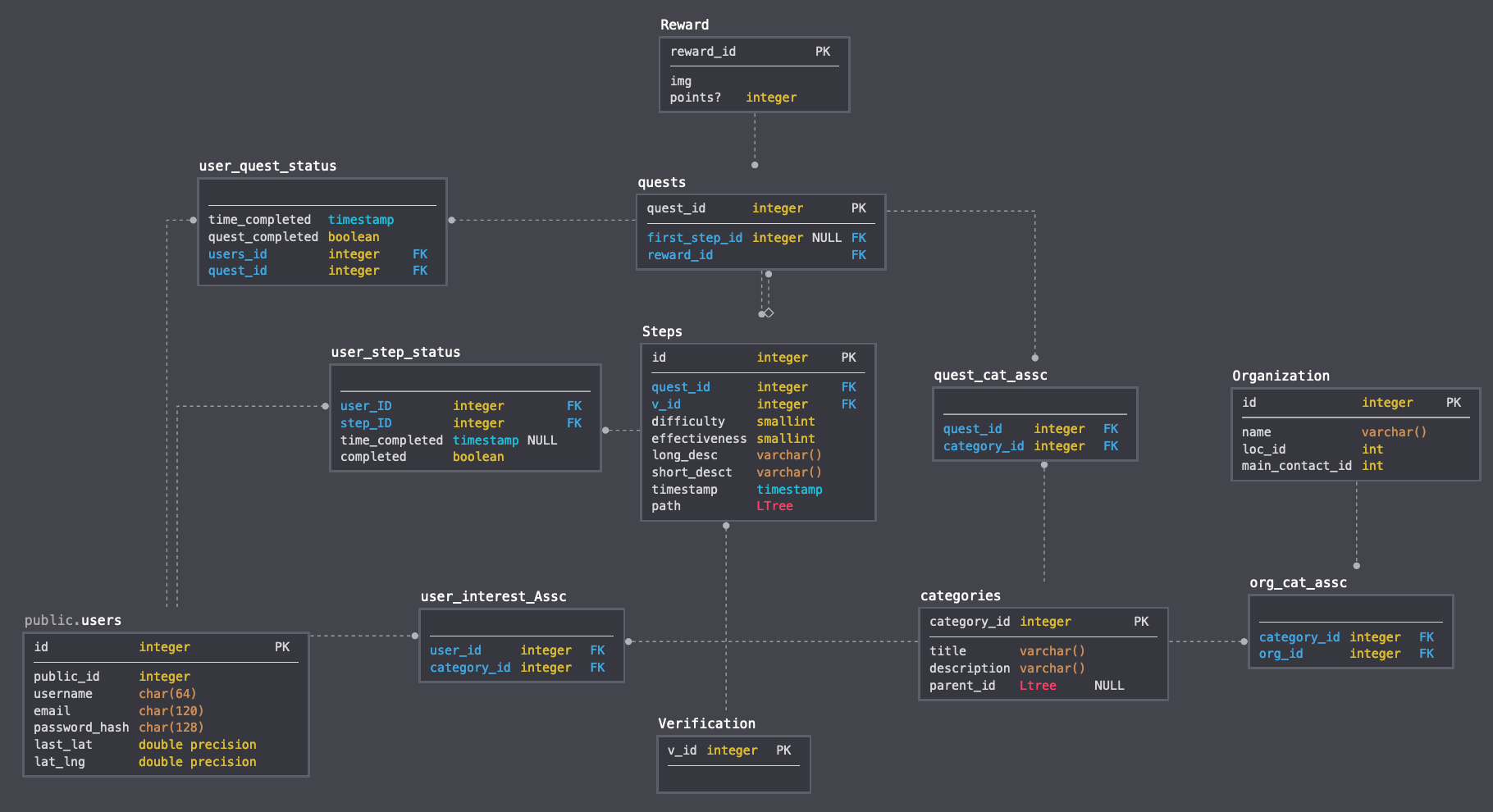

I’m working on a platform which will encourage users to go an get involved with non-profits or causes that they care about. I intend on building a fully working API which might look something like this.

Furthermore, I want to add a Redis layer to cache responses and serve users results much quicker, as well as better Auth0 integration to better support user authentication and security. With a completed API, I will then try and design a react-native app that will give users “Quests”, or a series of steps toward a goal. They will complete these steps, and they could be verified in a variety of ways, and receive a reward (like a badge or something). The idea would be teaming up with non-profits dedicated to sustainability in many different forms, and get people out and about to complete their quests. By gamifying and simplifying the act of doing a good deed, it might be possible to get people motivated to get involved.

Wish me luck!

Bibliography and Excellent Flask API Resources

- Real Python Flask By Example (Best Reference)

- SQLAlchemy — Python Tutorial

- Beginner’s Guide to Using Databases with Python: Postgres, SQLAlchemy, and Alembic

- A Massive Guide to Building a RESTful API for Your Mobile App

- Creating Web APIs with Python and Flask

- Flask API Starter Pack

- Building a RESTful Blog APIs using python and flask - Part 1

- Managing Hierarchial Data in SQL

- Modeling PostGres Trees with LTree and SQlAlchemy